|

| Colour Processes in British Cinemaduring the 20th Century |  |

||||||||||||

|

Biocolour; Dunningcolor; Cinechrome; Gasparcolor; Kinemacolor; Lee-Turner Colour; Raycol; Spectracolor; Technicolor Colour processes are divided into two categories: Additive and Subtractive. Additive systems require the projection of 2 or 3 single-colour images that add together to create a multi-coloured image. In Subtractive systems the projected film contains the multi-coloured image, the colours being subtracted from the white light of the projector. Lee-Turner Colour 1899-1903Lee-Turner Colour was submitted for patent in 1899 (patent was granted the following year) and was the first demonstrated motiom picture colour system. Invented by Edward Raymond Turner, who lived in the West London borough of Hounslow, and backed by the cricketer Frederick Marshall Lee, it was an additive process in which a rotating set of three filters exposed successive frames of black and white film to a red-filtered, green-filtered and blue-filtered image. A special projector showed each frame, through the appropriate colour filter, with the next frame and the previous frame, also appropriately filtered, superimposed over it. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

The Lee-Turner projection system. As each frame is pulled down the filter wheel turns to the next set of filters. In each set the colour sequence moves down, so the correct colour remains with the frame. The three lenses are adjustable to enable the three frames to be superimposed. In 1902 Charles Urban, an American who had settled in the UK to become a major moving picture distributor, bought out Lee and continued funding development of the system. After Turner suffered a fatal heart attack in 1903, Urban hired filmmaker George Albert Smith to continue the work. But the process was beset with problems: in movement the difference between the three images caused colour fringing. (The ideal solution, that of exposing and projecting three frames at a time was physically impossible - the film could not be moved that fast, with that great a pull-down distance.) Moreover, the weave inherent in motion picture photography meant that the three frames were never perfectly superimposed but shifted constantly against each other. Instead, Smith concentrated on a two-colour system.

Kinemacolor 1909-1917Our eyes provide the sensory input, but we "see" with our brains – meaning that the brain does a great deal of processing to tell us what we are looking at. One of these processes is colour compensation – the mind adjusts the colour range we see under artificial or unnatural lighting conditions to look the way experience tells us it should. Hence, if the colours have an orange bias we will see grey areas as having a blue quality. Working for Charles Urban, George Albert Smith seized on this effect to patent a 2-colour additive system in 1907, using rotating red & green filters to expose alternate frames of film coated with panchromatic emulsion and shooting at twice the normal speed (around 32 frames per second as opposed to 16) to allow persistance of vision to 'mix' the colours, and also reduce colour fringing. Projection was through a similar rotating filter, at the same speed as shooting. Test films were shot, trying out a range of cyan/green and amber/red filters on different subjects. On 1 May 1908 the Charles Urban Trading Company moved into new premises, Urbanora House in Wardour Street (the first film company to settle in what would come to be known as London's Film Row) and Urban used the event as an opportunity to announce the current production of the first films in 'natural colour' – as opposed to the hand tinting that was currently used. On 26 February 1909 the Urban-Smith Natural Colour Kinematography process, now named Kinemacolor, was launched with a 'special invitation' matinee programme of 21 colour films shown at the Palace Theatre, London. Despite the persistence of some colour fringing on fast actions Kinemacolor proved a great success, and Urban bought out Smith's rights to the patent and started the Natural Color Kinematograph Company to manage production, its offices and processing laboratories occupying the building on the opposite side of Wardour Street from Urbanora House, and duly named by Urban Kinemacolor House. It was decided not to offer the system for general use but to retain production within the company. Despite the extra expense of the specialised projector and of twice as much film per minute (at a higher print cost) than ordinary black and white films, Kinemacolor films were in high demand. While cinemas might be reluctant to install a new projector, theatres were happy to hire them for special presentations, appealing to a middleclass audience who could afford the higher prices. This audience also approved of Urban's philosophy on subject matter – "To entertain and amuse is good; to do both and instruct is better" – to which end he dispatched Kinemacolor cameramen worldwide. Colour films of the funeral of Edward VII (1910) and the coronation of George V (1911) boosted the reputation of the process at home and abroad, and Urban topped them all with his 1912 release With Our King and Queen Through India, a set of colourful documentaries showing the royal tour of 1911 and culminating in the Delhi Durbar to celebrate King George's coronation as Emperor of India, the total presentation lasting around two and a half hours. In 1911 a company called Biocolour started producing films using a process similar to Kinemacolor, with the exception that instead of the projector being fitted with rotating filters the frames of the film print were stained alternately red and green, a process devised by the photographer William Friese-Greene. Urban immediately took out an injunction against Biocolour for infringement of patent rights. In 1913 the users of the Biocolour process, having now become Bioschemes Ltd, challenged Kinemacolor's patent in court. lnitially upheld, the patent was found invalid on appeal; the judge deciding that since it did not actually reproduce the colour blue it did not achieve its claim to reproduce the natural colours. This meant that Urban had lost exclusivity for the 2-colour process. Rival systems appeared and Kinemacolor went into decline. In 1915 Urban produced an epic 2-hour documentary for the British War Propaganda Bureau entitled Britain Prepared with the last part, showing the British war fleet, in Kinemacolor. It was intended to impress neutral countries, particularly the USA, with Britain's military capacity and Urban was incensed when it was decided to distribute the film abroad without the colour section on the grounds that the techical complications of projecting Kinemacolor would limit its appeal.

Biocolour 1911-1928Biocolour, an additive process devised by the photographer William Friese-Greene, was similar to Kinemacolor in that it used rotating red & green filters to expose alternate frames of film coated with panchromatic emulsion, shooting and projecting at twice the normal speed to allow persistance of vision to 'mix' the colours, and also reduce colour fringing.The difference was that instead of the projector being fitted with rotating filters the frames of the film print were stained alternately red and green. This meant that the films could be shown using a normal projector, just cranked faster. In 1911 former Kinemacolor cameraman Colin Bennett headed a company called Biocolour Ltd and started producing colour films. Urban immediately took out an injunction against Biocolour for infringement of patent rights. In 1913 the users of the Biocolour process, having now become Bioschemes Ltd, challenged Kinemacolor's patent in court. lnitially upheld, the patent was found invalid on appeal; the judge deciding that since it did not actually reproduce the colour blue it did not achieve its claim to reproduce the natural colours. By defeating Kinemacolor's patent Biocolour had opened the way for other 2-colour processes. The outbreak of war in 1914 put colour on the back burner, and neither Kinemacolor nor Biocolour were in much demand. After the war Frieze-Greene's son Claude made improvements to the process, and from 1924 to 1926 he filmed a 26-part series of travelogues entitled The Open Road, touring Great Britain from Land's End to John O'Groats and concluding with London. The series failed to generate further interest in the process as it still suffered from colour-fringing and flicker, and better processes were becoming available.

Cinecolorgraph 1912The Cinecolorgraph process was a subtractive process invented by Arturo Hernandez-Mejia (a Venezuelan living in New Rochelle, NY, USA), featuring a print with an emulsion on both sides. Using a camera designed to expose two rolls of black and white film simultaneously, via a transparent reflector throwing a mirror image onto the second roll, and with one roll filtered red and the other green, he produced two negatives – one to be run through a printer in contact with the emulsion on the usual side of the print stock, and the other, the reverse image, to be run in contact with the emulsion on the reverse side. The emulsions were designed to be chemically coloured red and green respectively. Although Cinecolorgraph was not a commercial success it paved the way for future systems.

Cinechrome 1914-1925Colin Bennett worked on another of Frieze-Greene's ideas as a replacement for the Biocolour process for the benefit of his investors, developing a system using a prism in the camera to split the image into two, which were filtered orange-red and blue-green and placed side-by-side on a double-width film with a row of perforations down the centre in addition to those at each edge. The resulting. print was projected via a double-gated projector which filtered the images the appropriate colour and allowed them to be superimposed on the screen. The process was known by Frieze-Greene's original name of Cinechrome and the backers of Biocolour formed Cinechrome Ltd to exploit the process. Bennett returned to his previous occupation of journalist, but others worked on improving Cinechrome. Technicolor from 1916Technicolor I (1916-1920);Technicolor II (1922-1927);Technicolor III (1927-1932);

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

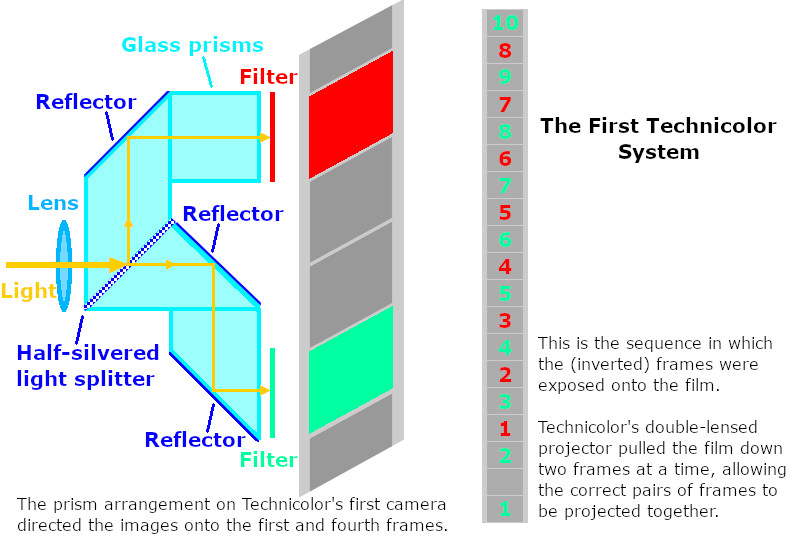

In 1917 they took their processing laboratory, a speciall equipped railway carriage, to Jacksonville, Florida, to shoot a feature film, The Gulf Between, to demonstrate their system. They arranged to show the film in a succession of Klaw and Erlanger theatres, but during the first week in Buffalo it became evident that the mechanism for adjusting the twin lenses of the projector to align the two images on the screen was just too fiddly and unreliable to be commercially viable.

It was a disappointment, but Process Number One had provided them with the beam-splitting system that would be central to future camera design. Rather than waste time and money trying to perfect the system, Kalmus decided move on from the additive projection process and focus on the next step – the problem of creating a coloured print, that could be shown on a standard projector.

Technicolor II (1922-1927)Finding the rail car processing laboratory rather cramped Kalmus had a new laboratory built in the basement beneath the Boston offices of Kalmus, Comstock & Wescott.

Previous subtractive systems, such as Cinecolorgraph, had used positive stock with emulsion on both sides, so that each side was printed with a matching image and dyed the appropriate colour, one side red, the other cyan/green. The Technicolor team concentrated on the imbibition method, whereby dye was absorbed by the gelatin layer.

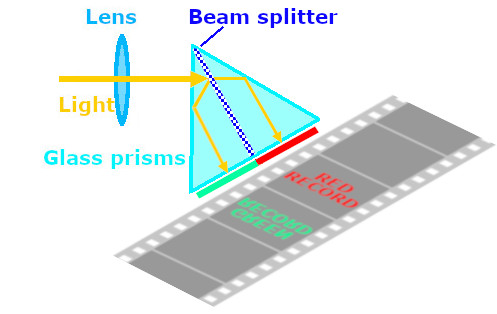

A camera was built which exposed the area of two frames of film at a time, with a prism system that split the image in two, placing one image on the first frame of film and a relected image upside down on the next frame. This produced a negative that could be skip-printed to give a positive print of the the first set of colour-filtered images, then turned upside down to make another positive print (reversing the order of frames) consisting of the second set.

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

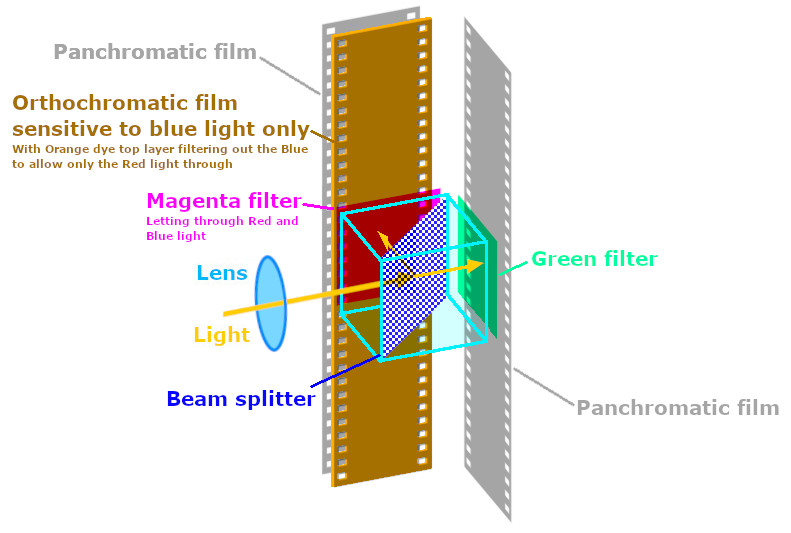

The positive prints were made on special film half the thickness of standard film. the two prints were then cemented back-to-back (the reason for one image being the reflection of the other) with the frames and sprocket holes in perfect registration. A subsequent "tanning" process hardened the gelatin holding the image. When the silver halides were removed and the non-hardened gelatin washed away a relief image remained, of hardened gelatin the thickness of which varied according to the tone of the original image. The two sides were then passed over baths of the appropriate dye – the thicker the gelatin, the denser the concentration of dye absorbed. Because the gelatin matrix was formed from a positive print it was effectively a negative – thickest where there was none of the filtered colour present and thinnest where there was the most of the filtered colour. It was therefore dyed the opposite colour – cyan/green from the red record, red from the green record. The exact tint and intensity of the dye could be minutely adjusted to achieve the ideal colour balance for each scene. It would seem the original idea was for the two films to be cemented face to face, so that the film on both sides should protect the image from scratches, but they found that this idea had already been patented, by William Van Doren Kelley, the inventor of the various Prizma colour processes. However, back-to-back cementing allowed them to save time by processing the two strips together. On a trip to New York Kalmus persuaded trial lawyer William Travers Jerome to invest in the new process. Jerome introduced more investors, and also interested the movie magnates Marcus Loew and Nicholas M. Schenck, and Joseph M. Schenck. While they were not prepared to invest money in the process, Joseph M. Schenck agreed to oversee the production of a feature film, The Toll of the Sea, providing the use of his Hollywood studio, the director Chester Franklin and the star Anna May Wong, free of charge. The film premiered at the Rialto in New York 26, 1922. The demand for bookings was greater than the Boston laboratory could handle and it did not go on general release until the following year, when it grossed $250,000, of which nearly two-thirds went to the Technicolor production company. The rest of Hollywood was watching with interest. Technicolor's cameraman Ray Rennahan shot several inserts for Cecil B. DeMille's In November 1923 Famous Players-Lasky used Technicolor for their production of Zane Grey's Wanderers of the Wasteland, which prompted Kalmus to open another Hollywood laboratory to handle the demand for daily rushes. It also prove successful. The previous films had been shot out-of-doors under natural light, as the higher lighting levels required for the colour process meant hotter conditions in the studio, causing some actors to complain. The Technicolor team were delighted when asked to shoot two dream sequences for Samuel Goldwyn's First National Pictures feature Cytherea. These were critically acclaimed, but Hollywood was still reluctant to commit to colour. A Technicolor team went to Rome to shoot scenes for M-G-M's Ben Hur (1926), but little of the footage was actually used. Several other films, including The Phantom of the Opera, included one or more colour sequences. Then in 1925 Douglas Fairbanks, who had always admired the process, decided his next film, The Black Pirate, needed colour to catch the 'spirit of piracy' found in the posthumously published collection of stories and illustrations, Howard Pyle's Book of Pirates (1921). Fairbanks' desire for the colour to work to the benefit of the production was the commitment that Technicolor was looking for, and they worked tirelessly to achieve the best results. To establish the color key for the picture, Kalmus later explained, test prints were made at six different color levels, "from a level with slightly more color than black-and-white, to the most garish rendering of which the Technicolor process was then capable." To ensure the coloure was an enhancement and not a distraction a slightly muted, 'painterly' palette was selected. Fairbanks had over fifty thousand feet of film shot, over a four month period, to test color keys, make-up, fabrics, and locations, at a cost of around $125,000. Two sets of costumes and makeup were created to accommodate the colour differences when filming in natural and artificial light. Shooting started on location around Catalina Island, with a specially constructed pirate ship, but the backgrounds did not photograph to Fairbanks' satisfaction, and most of the film was shot on the United Artists' backlot, with cinematographer Henry Sharp working closely with Technicolor’s own cameraman, George Cave. The Black Pirate cost around one million dollars, a staggering sum for the production of a motion picture in 1926, but, a critical, artistic and popular success, it ultimately grossed $1.8 million domestically. Although Fairbanks included some Technicolor scenes in later films, he never attempted another complete colour feature. There were several problems with the process. Matching the dyes to get the right colour balance for each scene was time-consuming and wasteful. Heat from the projector lamp could soften the cement and projectionists complained about the film curling, or 'cupping,' causing difficulty with focusing. Prints were returned to Technicolor who 'ironed' them flat again. More serious were cases when the two films actually separated. A long-term problem was that the magenta and cyan elements of the dyes were fugitive and faded completely over time, leaving a yellow-coloured print. This was not so serious, as release prints were only expected to have a short life. Further films were made with colour sequences, but only one complete colour feature, The Joy Girl (Fox, 1927) a comedy starring Olive Borden. Meanwhile the Technicolor research department worked on an improved release printing method. Technicolor III (1927-1932)The third Technicolor process used the same camera as Technicolor II (see above), splitting and colour-filtering the image to produce a negative with two images on adjacent frames, the inverted green-filtered frame directly below the red-filtered one. The step forward was in the printing stage, where two gelatin relief films were used to transfer their dye onto blank gelatin-coated film, one after the other. Both colours were printed on the same side (requiring the mirror image to be reversed on the optical printer) giving a two-colour print that could be run through any projector the same as a black-and-white one. This had long been seen as the goal, but required a lot of development to become workable. It took several minutes for the dye to transfer fully from the relief matrix to the print emulsion, during which time the films had to remain in close contact. The dye tended to spread out during this time, diffusing the image, so various dyes and inhibitors had to be tested. The perfected system used a 240-foot long continuously moving looped metal belt studded with registration pins to keep the dyed matrix and print films in register as they passed between rollers through a water tank for two minutes before separating, with the matrix being cleaned and re-dyed ready for the next printing and the newly coloured print ready for the secong colour transfer. A gelatin matrix was good for between forty and fifty prints before it needed replacing. Between the dye bath and contact with the blank film, the matrix passed over a series of water jets, which could be used to dilute the amount of dye held by the gelatin, a process called wash-back, allowing for precise adjustments for scene-matching. As each matrix was in effect the negative of the colour it represented, it was used to print the opposite dye – cyan/green from the red record, red from the green record. The announcement of the new process coincided with Hollywood's adoption of sound. This was initially an extra problem, but the simplest solution was to process the soundtrack in the normal photographic manner on the otherwise blank film before the dye transfers. Natalie Kalmus, Herbert's wife and a former art student, headed the company's color consultancy department, and personally advised studios on the use of colour, both in terms of practical reproduction and in dramatic and psychological use. Process III proved to be a run-away success as US producers thought colour would be the natural successor to sound. However, Technicolor was unable to keep up with the initial demand, and producers soon found that the new realism opened up by sound was enough for their audiences, who saw colour as an bit of a gimmick. By the end of the decade US colour production was in rapid decline. Technicolor IV (1932-1953)Technicolor III was a successful two-colour subtractive system with both colours tranferred by matrix to one side of the print. The next step was the three-colour system necesary to reproduce the full colour spectrum. To produce the three colour records needed, a beam-splitter divided the image into two. One went straight on through a green filter to expose the green record on ordinary panchromatic black-and-white stock. the scond image was reflected and passed through a magenta filter (allowing both red and blue light through) to expose two films travelling together (bi-pack) emulsion-to-emulsion so that the image was focused at the point that the emulsions met. The first film was a special orthochromatic emulsion sensitive only to blue light, therefore providing the blue record. This film also had a final coating of orange dye. The light entered through the base and travelled on through the emulsion but the blue content was blocked by the orange dye and only the remaining red light exposed the second film, which was again normal panchromatic stock. The three reels of stock were housed side by side atop the camera with the take-up reels similarly in parallel beyond them. The stock for the red and blue records were engaged together on the film gate take-up sprockets, and allowed to twist freely through 90 degrees from and to the reels.

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

The soundtrack was processed normally in black-and-white on the print stock, along with a very pale version of the green image record. This gave a light grey "ghosted" version of the image, which helped define and crispen the final image, as was often employed in the paper print industry. This print was then prepared with a coating of gelatin, with a little albumen added to inhibit the dye from spreading, and coloured by dye-transfer from the three matrix films. As each matrix was the negative of the colour value that created it, it was used to transfer the opposite (complementary) colour dye – the blue record carried the yellow dye, the red record carried the cyan dye and the green record carried the magenta dye. They were transferred in that order, as there was a tendency for the transfer process to smudge the previous dye. The definition of the yellow layer was least important to the crispness o the image, and the magenta was the most important. Interest in colour was at a low ebb among Hollywood studios in 1932, so interest needed to be stimulated. On the other hand, in order to cope with the expected demand for the new system, Bell and Howell, who manufactured the cameras for Technicolor, needed time to provide a sufficient number of new cameras. Since animation studios could use their normal rostrum camera to provide the necessary three colour records on one reel by shooting each frame three times, rotating the three filters, Technicolor boss Herbert T Kalmus approached various animation studios with his system. Only Walt Disney was prepared to try the new system, with its added cost and need to experiment with coloured paints, as a means of improving the sales of his Silly Symphony series, which was not performing as well as hoped. The Silly Symphony currently in production, Flowers and Trees, was re-worked as a colour cartoon, and proved a great success, going on to win an Academy Award. Disney contracted with Kalmus for exclusive use of Technicolor in animation for the next 2 years, and used it for all subsequent Silly Symphonies. Other animation companies could only compete by using the available 2-colour systems. By the time the exclusivity contract expired Disney had created a demand for coloured cartoons. Apparently Technicolor insisted on shooting the animation themselves – presumably they were anxious to ensure that camera registration, filters and lighting levels were not compromised to the detriment of the system. Some further Symphonies may also have been shot by Technicolor, but eventually Disney had the revolving filter disc installed on his own camera. Kalmus next persuaded Pioneer Films to make a live-action short, La Cucaracha (1934), in the 3-colour process, and commit to making a series of features. With the success of La Cucaracha and Pioneer's first feature Becky Sharp Hollywood welcomed Technicolor with open arms, while Kalmus and his team continued to improve the system. While it could be toned down as required, the principal attraction of the process was its ability to show a very vivid colour palette, suitable for fantasies and emotional or melodramatic productions. These extreme values gave the process its advertising slogan – Glorious Technicolor. Technicolor insisted on total control of its product. The special beamsplitter cameras had to be hired directly from the company, and their technicians and colour consultant (Kalmus's ex-wife Natalie, with the power to veto the chosen colours) were aways present on the set. In 1935 Alexander Korda, who had been a Hollywood director in the late 1920s and whose UK production company London Film Productions was constructing a studio complex at Denham along Hollywood lines after the success of The Private Life of Henry VIII and subsequent features, persuaded Kalmus to build a Technicolor processing laboratory near Denham. Not only would this plant process colour film for Denham, it could also provide the release prints for American films to be shown in Britain, and, being located close to London's Heathrow Airport, it could quickly process and return film from Europe. The British affiliate Technicolor Ltd was promptly formed, and the new laboratory was opened the following year. The first Technicolor film to be made in Britain, Wings of the Morning, started shooting at Denham studios in July 1936 starring US actor Henry Fonda and French actress Annabella as a horse trainer, in Ireland to prepare horses for the Epsom Derby, and the granddaughter of a Spanish gypsy and an Irish nobleman, visiting Ireland with her grandmother. (The plot combined two short stories together and Annabella played both the young gypsy, whose aristocratic husband, played by Leslie Banks, dies after a riding accident, and the granddaughter, with a fianc%eacute;e in Spain, who falls for the handsome young trainer.) Unfortunately the laboratory was not yet ready, so each day's filming had to be sent to Hollywood for processing. London Films produced a Technicolor cartoon short The Fox Hunt in 1936. After the success of Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Korda put a feature-length cartoon based on Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days into production, but it was halted on the outbreak of War. A reel of Technicolor negatives was found in 1955 and used, with additional animated maps and other linking material, to create a short version, Around the World in 18 Minutes. The British Technicolor had the autonomy to pursue its own research, experimenting with other dye and emulsion chemicals. It gradually developed its own British colour sensibilities, and some of its discoveries were taken up by the parent company. Technicolor V (1954-)The development by Kodak of Eastmancolor in the 1950s resulted in a single chromogenic film that processed as a full colour negative, doing away with the need for a three-strip camera. Prints could be made from the negative by the same process, but to preserve the original negative it was normal practice to make duplicate negatives from which to make the release prints, and this resulted in a notable loss of colour quality. The fifth incarnation of Technicolor just involved the laboratory making 3 colour-filtered matrices from the colour negative and using these to transfer dye to the print in the manner of the pevious system. For a long time Hollywood preferred to have their prints made by Technicolor for the vibrancy of its colour dyes.

Biocolour 1908-1915

The 1927 Film Act, which obliged British cinemas to show a quota of British films (7.5%) for a period of 10 years, had the effect of stimulating investment in the British film industry. When in 1932 Technicolor perfected a three-colour system and granted Walt Disney a 3-year exclusivity deal for animation production in exchange for showcasing the process in their Silly Symphonies series, the availability of investment led to an explosion of British colour systems.

SORRY, THIS PAGE IS STILL UNDER CONSTRUCTION.

Kinemacolor 1908-1915

Biocolour Keller-Dorian Cinecolorgraph Brewster Color (I)Chronochrome, a.k.a. Gaumont Color Prizma (I) Cinechrome Kodachrome (I) Technicolor (I) Douglass Color (Douglass Natural Color) Kesdacolor Prizma (II) Gilmore Color Zoechrome ColorCraft Polychromide Technicolor (II)Szczepanik Kelleycolor Color Cinema Corporation Lignose Naturfarbenfilm Busch Color Harriscolor Kodacolor (I) Raycol 1928-1935Raycol was the invention of Austrian chemist Anton Bernardi. A two-colour additive system shooting on ordinary black-and-white stock with a special lens attachment that split the image to two diagonal quarters of the frame area, one filtered orange, the other blue/green. The diagonal placement was to ensure that there was no fringing between the two images. Keeping the standard screen proportions, the image was the same size as that on 16mm film. The original trick was that the special projector lens which enabled the two images to be adjusted for accurate superimposition on the screen contained an pale orange filter only; the blue/green image was projected in unfiltered black and white. An effective illusion of colour was created by the brain trying to colour-balance the image. Patent

Spectracolor 1934-1937Spectracolor was a two-colour subtractive process, based on the German Ufacolor system, that was promoted by Publicity Picture Productions Ltd in 1934. Whether this was done by arrangement with UFA or the process was brought to Britain by emigrés fleeing the Nazis is unclear: certainly the latter was the case with another Ufacolor clone, Chemicolor [see below]. Faust was shown at the Curzon cinema, Mayfair, alomg with the first of the Cheery Chune advertising cartoons, Morris May Day, in April 1935 to introduce and promote the Spectracolor process. The first issue of The Cine-Technician (the magazine produced by the newly-formed ACT union) in May included the following item, presumably supplied by Hopkins: Spectracolor. The substitution of "Bi-Pact" for "Bi-Pack" (the running of two reels of film together through the camera gate - the films originally being spooled together in one 'pack') frequently occurs in The Cine Technician, suggesting a reporter or editor more familiar with the language of politics than cinematography. Dunningcolor c.1932-1939Dunningcolor was a two-colour subtractive process, the creation of father and son Hollywood technicians Carroll and Dodge Dunning, also credited with the Dunning travelling Matte system used in King Kong (1933). It used a specially built camera in which two separate panchromatic negatives ran side by side. The light from the source was split through two filters, with the red record registered on one film and the green on the other. An average of 65 per cent more light was needed and the camera had a built-in control system allowing for the cameraman to make adjustments depending upon the light source. Colour prints were made on single-coated stock by some special process by which the two negative exposures were seperately coloured. Not using bipack in the camera or duplicized (emulsion on both sides) print stock meant that the images of both colours remained in sharp focus throughout. Rushes from the red record could be printed in black and white and were suitable for release. In the UK processing was handled by George Humphries Film Laboratory in Charlotte Street, London. The color-prints are made on standard Eastman positive film: On standard black-and-white single-coated stock, not on duplitized (double-coated) film. This is done by a special process in which the two color-images are literally intermingled. The two negatives are both perfectly sharp. Their respective prints are not only sharp, but both lie in the same plane. Consequently, the resulting color picture is critically sharp on the screen. Rarely used for live-action, the process was adopted by Anglia Films, the animation studio set up by Archibald Nettlefold for Anson Dyer in 1935, and used with moderate success for the studio's series of entertaiment cartoon shorts, including the Sam Small series, narrated by Stanley Holloway. In 1937 a three-colour version of Dunningcolor was created, with the second gate of the camera running two negatives in bipack. The process was made commercially available in July 1939, but the outbreak of the Second World War seems to have prevented its exploitation in Britain. Gasparcolor 1933–1944Gasparcolor was an early three-colour subtractive process, the creation of Hungarian chemist Dr Belá Gaspar, working in Germany with the avant-garde film-maker Oskar Fischinger, who made the film Circles (1933) in Gasparcolor. Gasparcolor used a special film, manufactured in Belgium by Gevaert, which was coated with three emulsions all containing dyes. On one side the emulsion was sensitised to red light and contained a cyan dye, on the other two emulsions were sensitised to green and blue light and contained respectively magenta and yellow dyes. Processing required three black and white negatives of the action, filtered to provide the red, green and blue values. For live-action this required a camera capable of exposing three reels of film together, which were being made for the new three-colour Technicolor system, but for animation it only required each frame to be exposed three times, with a rotating three-colour filter under the lens. These frames could be separated into their three sequences by skip-printing in the laboratory. Three black-and-white positive prints were made from the negatives, and these positives were then printed onto the Gasparcolor film. During processing the dyes in the three layers were destroyed in proportion to the developed silver image, so that when the silver image was bleached away, three positive dye images were left. The soundtrack was printed with white light on the same side of the film as the magenta and yellow emulsion layers and developed separately. The soundtrack was therefore red on black, and required a slight increase in volume when projected. In 1934, with Hitler now Chancellor and the Nazis gaining support, Gaspar left Germany and settled in London. Here he formed Gasparcolor Ltd, with Major Adrian Klein, an artist, photographer and inventor with a particular interest on colour, acting as Technical Advisor. Klein demonstrated Gasparcolor to the Royal Photographic Society on 25 January 1935, and it was presented in Paris to the International Congress of Photography in July. It was widely taken up in Britain and Europe, primarily for cartoon films. George Pál, a fellow Hungarian, used it for the films he produced for Philips at Einhoven. In London it was used by Len Lye for Rainbow Dance and the advertising film for Shell The Birth of the Robot (both 1936). The advertising agency J W Thompson (London) commissioned advertising films from Pál, but preferred to have the black and white negative skip-printed for colour prints by Technicolor instead. When the Germans invaded Belgium in 1940 the supply of Gasparcolor film was cut off. With Britain under the threat of German invasion, Gaspar emigrated to the USA and arranged for Gasparcolor to be processed in Hollywood, with film manufactured in New York. However, the major studios were already using Technicolor and had no reason to change. Gaspar eventually sold his patents to Technicolor and 3M.

Gasparcolor is the first colour film positive material upon which the three negatives may be directly printed each in its own appropriate colour. For the first time, no dyes are used in the processing, no staining, colouring or toning enters into the treatment of the film. This sounds like a miracle, and in one sense it certainly is a miracle. Yet the principle is simple. Imagine three coloured emulsions. That is, emulsions which contain transparent dyes in suspension in the gelatine. These emulsions are coated on the celluloid in layers in the following order. On one side of the film we have the pink, and beneath the pink layer a yellow layer. On the other side of the film is coated a blue layer. Now these emulsions are so sensitized that we can print them with coloured lights each in turn, independently of the other.

Chemicolor 1936-39

Splendicolor Technicolor (III) Agfa bipack Horst Color Multicolor Finlay Harriscolor Cinechrome Cineoptichrome Dascolor Harmonicolor Hirlicolor Photocolor Pilney Color Allfarbenfilm Sennettcolor Sirius Color Brewster Color (II) UFAcolor, a.k.a. Vitacolor

Chimicolor

Magnacolor

Dufaycolor

DuPack

Rota Farbenfilm

Russian two-color system

AGFAcolor (I)

Cinecolor (I)

Technicolor (IV)

Morgana Color

Gasparcolor

Vericolor

Francita Process, a.k.a. Opticolor (UK)

Kodachrome (II)

Russian three-color process

Telco-Color

|